What was your process with Malou in creating “common ground[s],” which is set to Fabrice Bouillon LaForest’s nature-based score?

She came to Senegal, to L’École, and into my home. We spent time talking about experiences in common—being mothers, grandmothers. We talked about work, and found other things in common: We both ice our legs for arthritis in our knees!

We decided to bring all these themes into the piece and also the way we were responding to the environment. We found common ground there. Going on walks, Malou was drawn to stones and would collect rocks; I was drawn to trees, and I would collect sticks and branches.

I understand that this is the first time you’ve worked with a woman?

Yes, it’s the first time I’ve worked with a woman—to dance like this. It’s interesting, because it’s a white woman and a Black woman, but things [we have] in common are the problems, the joys, the issues that have to do with being a woman.

What has your attraction been to the “Rite of Spring” over the years—and, specifically, your having performed, in essence, a one-woman “Rite” choreographed by Olivier Dubois?

It’s a beautiful history. When I was the head of Mudra Afrique, there was an interest at that time of doing it. Béjart had done his version of “The Rite,” and we had these conversations about my doing the piece. I suggested a younger dancer—I was 35 at the time - to do the role of the Chosen One. He said, “No, you should do it.” We talked about it, but the piece never happened.

At the age of 70, when Olivier Dubois was 45, he said, “Do you want to do the “Rite,” and I said, “Yes.” It really was a big risk for both of us. I had to do it, because we talked about colonization, and in order to do this work, we were also very connected. There was an osmosis between us. I had to find such strength to do this piece because of the themes, but also because of the intensity of Stravinsky’s music. I had to bring so much of myself, my personality, and my strength and force into the work. It’s demanding.

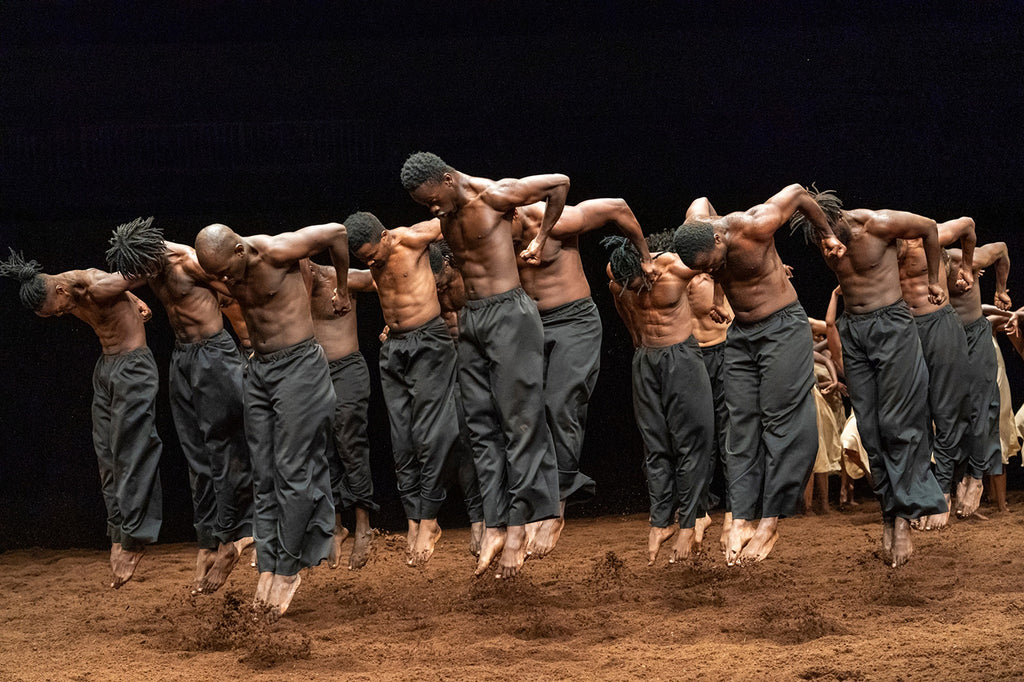

I first saw “The Rite” danced by the Paris Opera Ballet, and I noticed and sensed in the work that it was deeply African. Now that I’ve seen the [African] company do it, I’m really seeing them appropriate for themselves the music, and execute it with such precision and strength. I’m seeing that dance is so universal through this experience.

I understand that Pina’s point of departure for her “Rite,” was asking the question, “How would you dance, if you knew you were going to die?” What are your thoughts on that?

Death is not death. My piece with Malou, for me, Pina is there. For me, when people die, they’re not gone. They don’t go away. They’re in the wind, the water, in our flowers. They whisper to us. Pina and Stravinsky aren’t gone. They’re here. They’re so happy with what has come of this work, and they would be so satisfied, as am I, with the incredible physical and musical perfection that this company of dancers is performing. It’s truly different with this company, how it’s being performed. It’s truly sublime.

comments