Sweet Fields

According to artistic director Peter Boal’s welcome letter for Pacific Northwest Ballet’s fifth season program, the most popular mixed rep slates at PNB feature works by Crystal Pite or Twyla Tharp.

Continua a leggere

World-class review of ballet and dance.

One might easily mistake the prevailing mood as light-hearted, heading into intermission after two premieres by Brenda Way and Kimi Okada for ODC/Dance’s annual Dance Downtown season. Maybe this is just what we need to counter world events, you may think. But there is much more to consider beneath the high production values of this beautifully wrought program. Okada, for instance, folds a dark message into her cartoon inspired “Inkwell.” And KT Nelson’s “Dead Reckoning” from 2015 reminds us the outlook for climate change looms ever large.

Performance

Place

Words

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Already a paid subscriber? Login

According to artistic director Peter Boal’s welcome letter for Pacific Northwest Ballet’s fifth season program, the most popular mixed rep slates at PNB feature works by Crystal Pite or Twyla Tharp.

Continua a leggereLassoing is a surprising through-line for a Martha Graham Dance Company performance. The theme steps generally tend towards the child-birthing variety: contractions and deep squats.

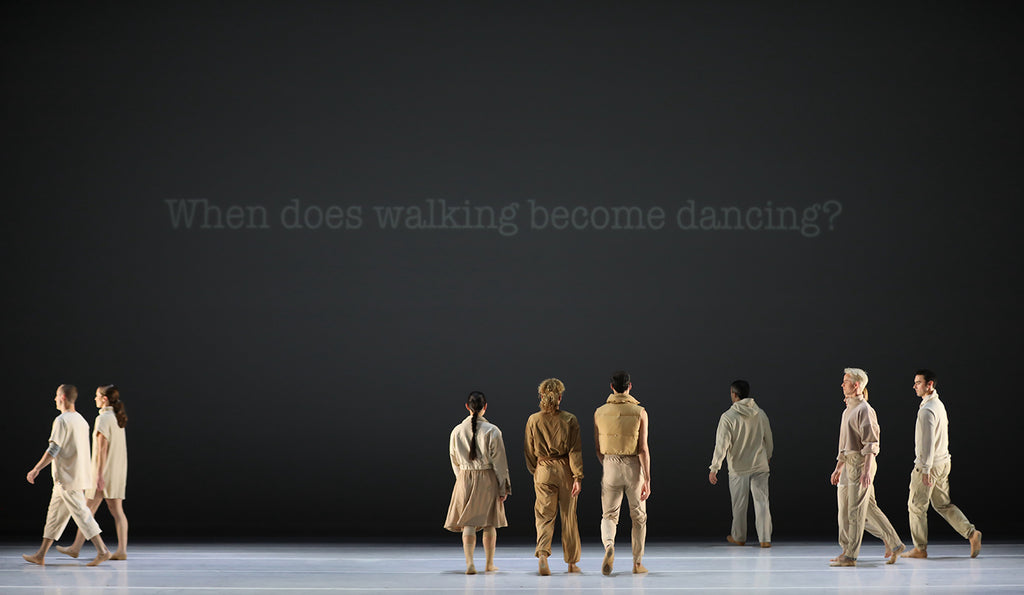

Continua a leggereAs a dance viewer, it’s easy to get swept up in the grand movements in a piece, glossing over the finer details.

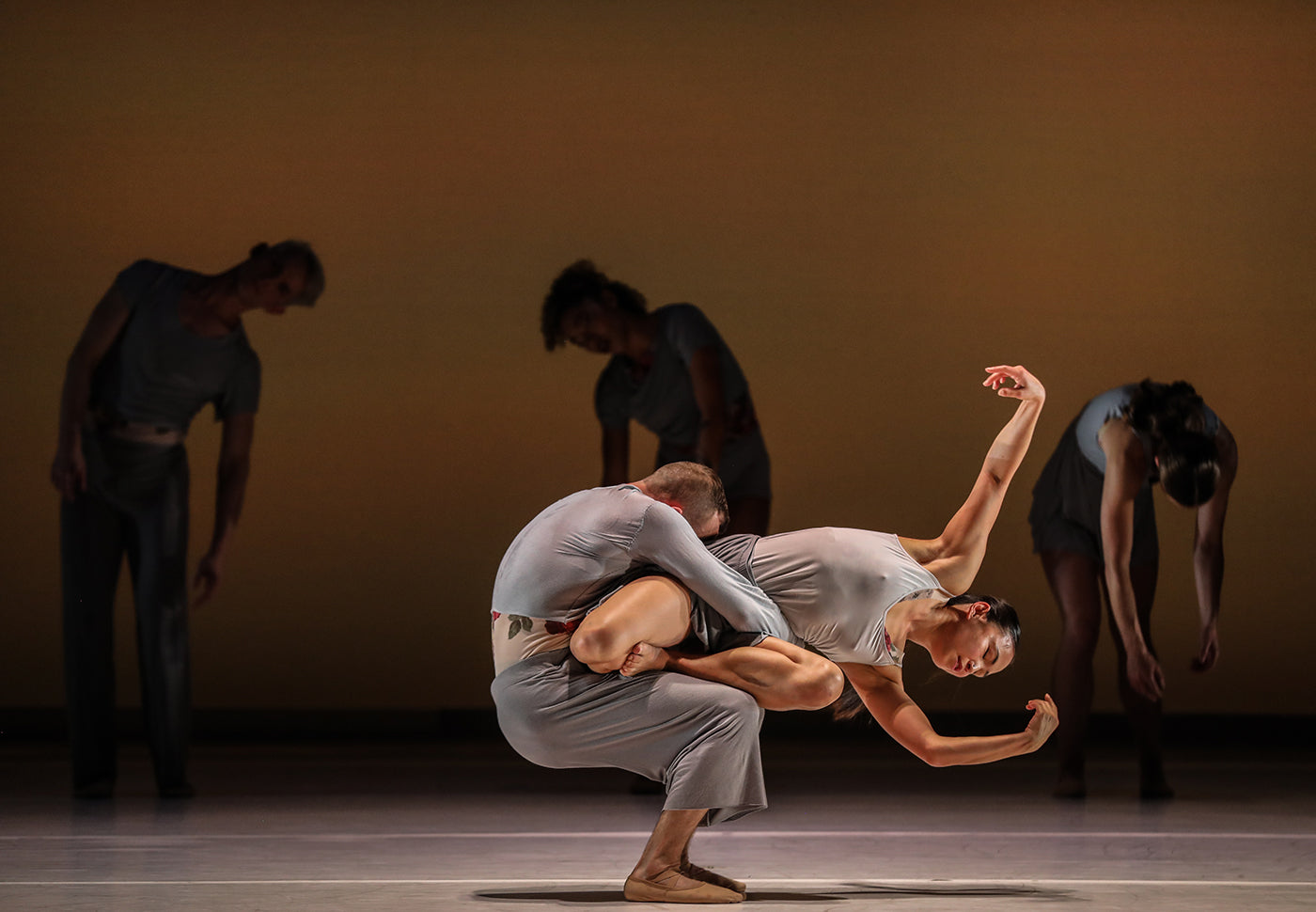

Continua a leggereHubbard Street Dance Chicago was in New York for a two-week run March 12–24 at the Joyce Theater, a venue that consistently programs excellent smaller dance companies in its 472-seat theater.

Continua a leggere

comments